When the world gets too crazy and everything is upside down you should consider starting again with the alphabet. That’s what the guys from

Devětsil did. It was just a couple of years after the end of WWI, in the early 20’s, and

Devětsil was a group of avant-garde artists from Prague, looking for their way.

Vitěszlav Nezval was challenging the meaning for each letter of the alphabet. Sounds weird? Think at the

Suprematists,

Malevich and all the others, and their

Victory over the Sun. Think at

Magritte, or

Jasper Jones. The whole art of the twentieth century put itself firstly in motion to search the meaning of objects, to come then to the language. Words were questioned, and the relationship between words and objects. The meaning of each word was challenged: to be refined, consolidated or even redefined. It was the century of

Wittgenstein.

What

Suprematists did in

Victory over the Sun with words,

Devětsil did with letters, in their

Abeceda.

Vitěszlav Nezval wrote for each letter a small poem, excited by

the intellectual gymnastics afforded by poetry’s most immediate object: letters. He focused on their visual suggestiveness. A was reminding him of a

simple hut, C was reminding him of the crescent. As for S, this was associated with snake charmers, snake dancers and syphilis (which could have been the unfortunate result of too close encounters between charmers and dancers):

On the plains of darkest India

Lived John, a charmer of snakes.

He loved Alice, the snake dancer.

She kissed him too strongly,

He died of syphilis.

So, at the beginning was a poet. Then a ballerina came into picture:

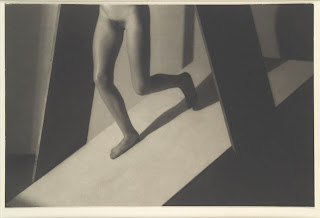

Milca Majerova imagined choreographic movements for each letter.

The dances needed to be immortalized. And the photographer came:

Karel Maria Paspa, author of some still images for each dance.

Much later, in 2000, a movie would be made with

Mayerova’s dances, Alphabet. The movie was done at the

Wolfsonian Florida International University, an institution trying to recreate the spirit of

Devětsil,

Bauhaus,

VKhUTEMAS… the avant-garde of the twenties.

But let’s come back to the epoch of

Devětsil. Someone was still needed for the building of

Abeceda, the Alphabet Book. This was

Karel Teige, who made the graphical design of the book, chose the images and decided on the layout for the poems of

Nezsval.

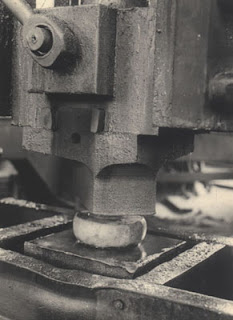

Teige was interested in the relationships between verbal and visual art, industrial technology and mass media. So, he respected the integrity of the text while playing with it now and then (as well as with photographs of the dancer and the letters themselves). What

Teige got was a poetic dialogue between text and images: and here is where the strange appeal of the book comes from.

Karel Teige would say later (in

Moderní Typo),

in Nezsval’s Abeceda, a cycle of rhymes based on the shapes of letters, I tried to create a typofoto of a purely abstract and poetic nature, setting into graphic poetry what Nezsval set into verbal poetry in his verse, both being poems evoking the magic signs of the alphabet.

Like so many avant-garde artists, Teige was a fervent Communist. And it happened with him what happened with so many avant-garde artists:

after welcoming the Soviet army as liberators, Teige was silenced by the Communist government in 1948. In 1951 he died of a heart attack, said to be a result of a ferocious press campaign against him as a 'Trotskyite degenerate', his papers were destroyed by the secret police, and his published work was suppressed for decades (Wikipedia).

-------------------------------------

The video on top of this post was created by

Larsen & Friends.

(Modernism in Central Europe)

(Modernism in Central Europe)